“Can we sign this electronically?”. You might be hearing this question more often these days. Here are some basic principles and practical points to help you answer this question under Scots law.

Two silos: Which one are you in?

There is a lot of jargon in the area of electronic signatures. Understandably, this may be off-putting and lead to a feeling of uncertainty when considering whether to sign documents electronically. But let’s start with the most fundamental building blocks. First, what is an electronic document?

In today’s world, there are two silos in which to categorise documents: traditional documents and electronic documents.

Traditional documents are signed on paper in wet ink and in hardcopy. Electronic documents are created in electronic form (eg. created and saved in a Word document) and signed electronically. Of course, traditional documents are often also created in electronic form, but the key difference is that electronic documents remain in that form. If electronic documents are printed after being signed electronically, what is produced by the printer is simply a copy of the electronic document. It is important to remember the difference between traditional and electronic documents, as there are different legal rules and considerations for each category.

E- signatures: Which type are you using?

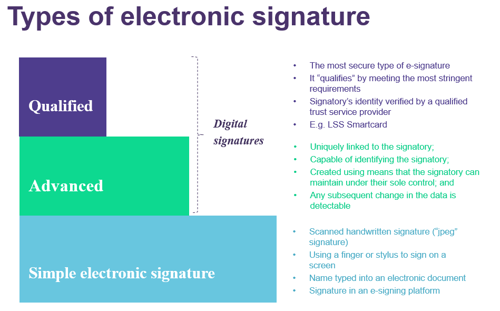

An electronic signature can only be applied to an electronic document. There are three types of e-signature: simple, advanced and qualified. Simple electronic signatures are currently the most common, and the most widely used type of e-signature. They are also the least secure, with advanced and qualified signatures benefiting from more integrity (see image).

Three concerns: Are you satisfied?

Subject to some exceptions, electronic signatures are valid under Scots law. This is because under the Requirements of Writing (Scotland) Act 1995 only certain categories of document need to be in writing. So most documents do not legally require a signature at all.

An electronic signature may be legally valid, but contract parties also need to be satisfied that they can rely on them. The parties should be comfortable with these three main concerns:

- Did the person whose name is on the document actually sign it?

- Was the e-signature or indeed the e-document interfered with after it was signed?

- How do we prove these two points?

Simple e-signatures can be used in electronic signing platforms1, and these tend to provide more evidence of the signing process than other types of simple e-signature. The problem is that even when using a simple e-signature in an e-signing platform, it is difficult to prove conclusively that the actual signatory signed the document.

That task is easier with advanced and qualified signatures. Advanced and qualified signatures are “uniquely linked to the signatory” and “capable of identifying the signatory”2. This means that there is some reliable evidence that the person whose name is on the document actually signed it. Advanced e-signatures (AES) are also “created using means that the signatory can maintain under their sole control” and any change to the signature is detectable. This means that if there is an attempt to tamper with the signature, this will be clear to anyone reviewing the document afterwards.

The qualified e-signature (QES) in addition has had the actual identity of the signatory verified by an independent party, eg. a qualified third party has checked the signatory’s passport or driver’s licence. That is why a QES is the most secure and most reliable type of e-signature. A QES has the equivalent legal standing to a wet ink signature3 and is self-proving4. It will address the three concerns to the greatest extent.

QESs in e-signing platforms are only just becoming more widely used in Scotland. There can be timing issues in obtaining a QES and they usually involve greater costs. AESs appear to be even less often used at the moment, although they generally don’t suffer from the same timing and cost issues. When evaluating e-signing platforms, it may be worth considering their AES offering, in particular if AES is included in the proposed package at no or little extra cost. Using an AES instead of a simple e-signature offers a higher degree of security.

In using this terminology, take care around the difference between electronic signatures and digital signatures: digital signatures involve the signature being encrypted and hard-wired to the document itself. QESs and most AESs are digital signatures. Simple signatures are electronic signatures. Digital signatures will provide more evidential weight than electronic signatures because they can satisfy the three concerns: they give greater assurance of the signatory’s identity and the document’s security, and the evidence to prove it.

Four top tips on electronic signatures:

At Burness Paull we have been helping clients to navigate the world of electronic signing amid the challenges of lockdown restrictions. Here are my top tips when using e-signatures.

- All parties should agree early on in the transaction whether electronic signatures will be accepted. Avoid the scenario in which a completion deadline is looming and one party has signed electronically but the other party does not accept this. It makes life a lot easier if the parties agree on this point as early as possible and well in advance of the signing day. This agreement should be documented, eg. in email correspondence.

- Witnessing the e-signature does not make it self-proving. The regulations in Scotland5 stipulate that the only way to have a self-proving signature is by using a QES.

Many of us are used to obtaining self-proving signatures on traditional documents as a matter of course. We have our usual signature blocks set up with space for a witness to sign. But using these same signature blocks in an electronic document can be confusing because having a witness sign to attest a signatory’s electronic signature might seem to make that signature self-proving – it does not.

However, this issue might open the door to a consideration of whether the document needs to be signed in a self-proving way. Many commercial contracts are not required to be self-proving – they can be signed in a valid manner and that may be sufficient for the parties of that particular document. - Check the dates. A document may contain a variety of different dates: it could be signed by the parties on different dates, and the date on which the parties wish the terms of the agreement to be legally effective may be an altogether different date. There may also be defined terms in the document such as Effective Date or Completion Date. E-signing platforms can be used to generate a date in an agreement automatically. The significance of each of these dates must be clear in the document so there is no possibility of confusion.

- Go for it: this is the way the legal world is heading. Law firms in Scotland are using electronic signatures more and more often. The LSS has published a guide on the use of electronic signatures which explains the issues simply and thoroughly. Give it a try!

This article covers electronic signatures under Scots law. The law in England and Wales is different and separate advice should be taken when advising on English law documents.

You can also download Burness Paull's electronic signature guide here.

This article was first published in the Journal of the Law Society of Scotland, October 2020 issue.

1 An example of an electronic signing platform is DocuSign

2Articles 3(11) and 26, Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 (eIDAS)

3 Article 25, eIDAS

4 Regulation 3, The Electronic Documents (Scotland) Regulations 2014

5 Regulation 3, The Electronic Documents (Scotland) Regulations 2014

Related News, Insights & Events

Error.

No results.

The risk landscape in 2026: Key issues and how to manage them

18/03/2026

This event explores key risks facing your organisations and provides practical guidance on what you can do to best protect your business and ensure its resilience.

Property Risk Conference - Navigating Change in Commercial Property

05/03/2026

Join us for our property risk conference, a morning seminar bringing together legal and industry insight on the key risks and opportunities shaping the commercial property sector.

M&A Deal Insight Report

18/11/2025

Our annual M&A deal insight report, offering comprehensive analysis and insight into key market trends and evolving deal dynamics, based on what we have experienced over a 12 month period.

{name}

{properties.pageSummary}

{properties.headline}

{properties.pageDate|date:dd/MM/yyyy}

{properties.shortDescription}

{properties.eventName}

{properties.pageDate|date:dd/MM/yyyy}{properties.shortDescription}